The Great March on Washington in 1963 is a seminal American event. It is considered important enough to be taught in elementary school history classrooms a half century later, and it continues to receive attention through the awarding of doctoral degrees to those who study it. There are scores of books written about Aug. 28, 1963, and it has inspired many a successor march. It has proven as impactful as its organizers must have hoped.

Many organizations stood at the ready and sounded the alarm: the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Urban League and others, black and white. Religious organizations and African-American newspapers planned strategies, with civil rights leader Bayard Rustin orchestrating.

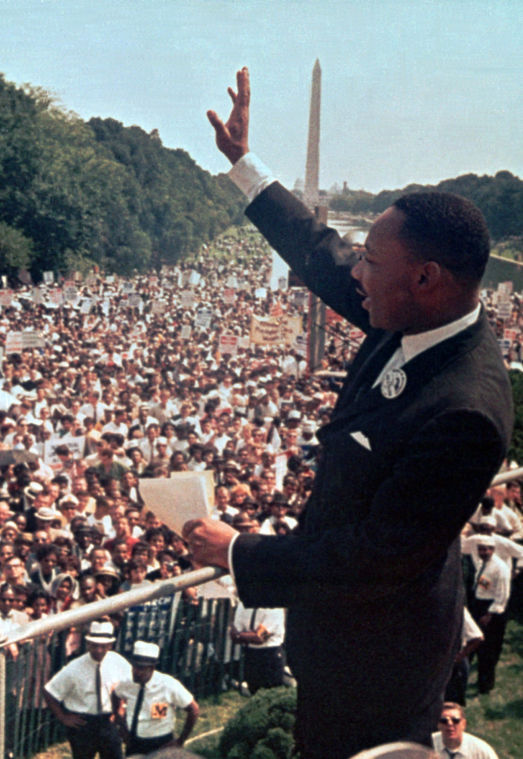

Martin Luther King, Jr. closed the day by delivering one of the most famous and inspiring speeches in the history of this nation. King told the country he had a dream of an America built on equality and opportunity — one in which every citizen’s rights was respected with civility.

Dr. King’s speech was such a galvanizing national moment for this country that it is difficult for many people to separate that day from the man and the words he spoke. Despite all the time spent teaching about the march and the ink used writing about it, most people mistakenly think of the March on Washington as a King-organized event. That is how blended his powerful speech and the march have become. And while his presence and voice helped to cement the march as a timeless moment, there is much more to remember about what happened that day and why it did.

Many have said the key organizer of the event, in fact, was A. Philip Randolph, the founder of The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Randolph was an important civil rights leader and organizer who deserves more credit than history has afforded him.

He had been among the group that conceived the march in the 1940s to put pressure on President Franklin Roosevelt to act more aggressively on civil rights. As they moved forward with the planning for a 1940s march, Roosevelt relented, and created the Committee on Fair Employment Practices. Randolph and his contemporaries agreed to hold the march in abeyance. By 1963, an older and wiser Randolph decided the time had come to make the statement he thought the march was necessary to make.

King probably wouldn’t like that his speech has come to overshadow such an important man as Randolph and his critical strategy for equality. I might go even further as to say that he likely wouldn’t approve of the fact that popular mythology boils so much of the Civil Rights Movement down to where he was on any given day. Cutting such intellectual corners creates too many nameless giants who put in the generations of work that led to Supreme Court victories, civil rights acts, my election as governor of Virginia and Barack Obama’s election as president.

The Civil Rights Movement was about extending the great promise of American goodwill to all citizens equally and serving as an international example that would inspire nations around the globe. It was not about a single person — even one as renowned as King.

No, the American Civil Rights Movement was about the great confluence of the American people and the Founders’ historic promise of justice for all.

King may have ended the day with an awe-inspiring speech that has stood the test of time, but that was not the purpose of the day. Randolph and his compatriots in planning the 1963 march had aims for federal attention and federal legislation that would broaden national equality. Yet, the core of what they wanted to do was to achieve their goals by highlighting groups at the local level and the issues/coalitions they were embracing in their home areas.

In essence, the intent of the march was to shine a national light on what was happening around the country, good and bad. That’s why Randolph and his fellow planners chose a preacher and civil rights leader from Georgia with the responsibility to close the August 28 proceedings.

In 2013 we must not look at the Great March in a vacuum — which often is what we are led to do. The march, in and of itself, was not a be-all/end-all.

Marching for the sake of marching, then just hoping it magically will result in progress, is foolish. The 1963 march was committed to ideals — it had goals and it had a purpose. It did not necessarily focus on Washington and what the federal city could be doing. Instead, it was about American communities far and wide. The march was about the principles laid down in America’s founding documents and the effort to make them universal. Importantly, it was about charging people around the country, all the people, with the responsibility of going out and making those principles universal.

Remembering the events of Aug. 28, 1963, is important, but no one should get too caught up commemorating just that one moment in time. We instead must focus on the ideals and aims of that era. We must assess the progress that has been made — and forge even further down the path.

Spend some time remembering what happened that important day. Then go into our communities and continue the work of implementing the nation’s promise of opportunity and equality. That is the true way to honor what that day meant.

And don’t forget the march’s official title: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Have we made progress? Absolutely, but the times still call for us to continue to strive for more of both.

The piece originally appeared in the Richmond Times-Dispatch on August 26, 2013:

http://www.timesdispatch.com/opinion/their-opinion/wilder-march-on-washington-charged-a-nation/article_8ca5885c-0d06-11e3-a7de-001a4bcf6878.html?mode=image&photo=0