(Speech Delivered August 16, 2011)

It is good to be in Martha’s Vineyard, and it is good to be back in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Twenty years ago I was settling into my second year as governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The country and the world were getting used to having a black American sitting in a chair many thought they might not live to see a person of African descent hold in this country. And I will say, it is an honor to be the first black person to have been elected to hold the office of governor of an American state.

But, I also want to say, for almost twenty years I was unsatisfied when people introduced me as the “first” black person elected governor in the United States. How can one have a first without a second? For too long, I was a caucus of one. Then in 2006, the voters of this state truly made me the first by adding a second, Governor Deval Patrick, who is now settling into his second term as chief executive of this commonwealth.

The election of one black governor is fine, but it could be an anomaly. The election of two is the beginning of a pattern. So I am happy to travel to Massachusetts, again. My home state, Virginia, was first, but often second can be as important to establishing a trend. Good of you Massachusetts for helping to set that trend in stone by electing — and re-electing — Governor Patrick.

Which brings us to 2011.

Since 1989, I have gotten a question I am sure Governor Patrick must have to answer constantly, as many of you in this room must often have to answer it: Have black people in America “arrived”?

Two black men have been elected governor of states. The United States Senate has counted black men and a black woman as part of its membership. Black men have sat — and do sit — in the leadership of the U.S. House of Representatives. I will point out that has been the case for both parties. And most glaringly and obviously, the people elected a black man to serve as president of the United States of America.

So, have we “arrived?”

I don’t think we will ever find the answer to that question by looking at political leadership data points.

The health and advancement of a community of people can’t be judged by whether any particular man or woman holds a single seat in a boardroom in New York or even an oval room in Washington. To do so is too easy, too lazy, and leaves too many people behind.

Our view needs to be more layered and more complex than that.

I do not minimize or denigrate the important electoral and governmental mile markers that note the advancement of black people in America, and truly the nation as a whole. It would be silly of me to do that, because it would minimize the great thing done by my close friends and neighbors in Virginia, not to mention by voters nationally two decades later.

But I do challenge citizens to take a broader view of how to judge where we as a country are on the road to providing full equality.

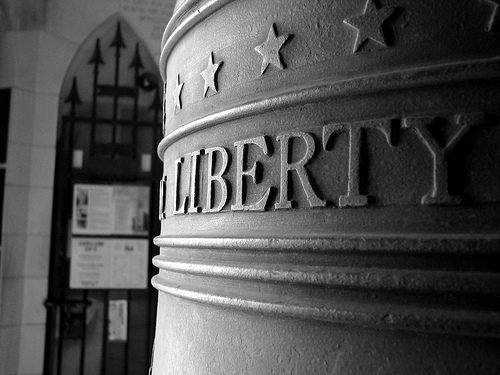

As slavery ended, the enunciation of the Emancipation Proclamation served as the ringing of a big bell. The sound of that bell announced to enslaved Americans in rebelling states that they were finally to be given what should be a natural right for all men and women, freedom.

But as our people were to see over the next few decades, despite President Lincoln’s proclamation being enshrined in the Constitution, it was not yet a full American freedom that had been bestowed in practical fact to match the beautiful words.

What was needed was a second ringing of liberty’s bell for black Americans. That happened in 1954 with the ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education, and continued through the 1960s with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Acts.

Has the bell been rung since then? Certainly it has. As I pointed out earlier, a former Confederate state elected a black governor, and the entire country elected a black president.

Those points in time represent a further ringing of the bell.

We must ask, though, are those events enough of a foundation for us to stand upon them and loudly to proclaim that black people in America have “arrived”?

While I honor the progress we have made on issues of equality — perhaps more than any other nation on the planet — the answer to that last question is, “No.” Despite all the great advancements of the past 150 years, full equality and recognition have not yet been met.

I stress that Brown and the election of a black president were great and necessary moments. But we must, as a people, recognize that eternal vigilance is the price of our American freedom.

We prize this nation’s mores and values that push us continually to live up to the ideal of freedom — sometimes despite ourselves — but they are not easy or to be taken as a given. We must work toward them everyday, otherwise they will wither.

No single event can or will cement freedom and equality alone. As vital as the Emancipation Proclamation was, it took many years of fighting and effort on the part of Americans, black and white — some of whom lost their lives during the struggle — before its words found real effect in the lives of many former slaves’ children and grandchildren.

I will go further and say it is wrong to look at a single event, even the election of a black governor or a black president, and say that event means black people or minorities of any hue have “arrived.” To do so would cause us to let down our guard — to lessen our vigilance. And were that to happen, American freedom would be in danger.

As a matter of fact, we must specifically acknowledge on a regular basis that no one event is enough for us to claim “arrival.” And in the process, we must use big, historic moments — such as the election of a black governor or president — to educate the next generation and beyond about what has been done and what still needs to be done.

This truly is a continuing project in community building that none of us has any right to cease. The question of the next few decades is how to march forward during this ongoing struggle.

What my generation and the president’s generation behind mine have done fairly well is demand and gain political power in the halls of Congress, in the states, and even in the nation’s executive mansion.

I learned, while serving for 16 years in the state Senate of Virginia, that the people always are ahead of the “leaders.”

The “leaders” said I was crazy to run for the state Senate in 1969 because no person of color had served in that body for nearly a century. The people proved them wrong.

The “leaders” said I was crazy to believe Virginia would be the first state in the Union legislatively to declare a state holiday for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Supposedly, the people of Virginia wouldn’t stand for it. It took me eight years to get both house of the Virginia General Assembly to pass it and to have a governor sign it — but it did happen. Did the people of Virginia riot in the streets? No. That holiday is celebrated to this day in Virginia in peace and harmony, befitting its honoree.

When I said I was going to run to be the commonwealth of Virginia’s lieutenant governor, there were cries followed by much anguish amongst the “leaders,” many of whom publicly called themselves my friends. They said my mere presence on the ballot would not only cause the defeat of the entire Democratic statewide ticket, but also the loss of the Virginia legislature to the opposing party. The people did not agree on Election Day — the entire Democratic statewide ticket won, and we maintained solid leadership of the General Assembly.

At each step, the “leaders” did not trust in their own people. The people, on the other hand, proved they were ahead of where those with honorifics and and titles believed them to be.

How has it mattered that people who look like me and my ancestors have attained political power? I would like to talk about some examples of how that has mattered.

(1.) When I became governor of Virginia, the Confederate flag was still used as an official symbol by the commonwealth’s National Guard. I decided that had to change. I didn’t set up a commission or have my counsel study it to death. I made a phone call and acted liked the state’s commander-in-chief. I asked the adjutant general of Virginia if my understanding of the use of the Confederate flag was correct. Once he acknowledged that it was, I informed him he would need to remove it in toto. He began the process of following that order within 20 minutes. There was no hand wringing or worry. There was only action, as I exercised the power afforded to me by the people of Virginia.

(2.) Many of you know the story of Allen Iverson’s arrest when he was a high school student, following a fight at a bowling alley where he happened to be the most visible person in the room. The arrest and conviction did not meet my definition of justice. I didn’t have to ask anyone whether I should right that wrong. I didn’t have to consult with experts about what to do. I had the power to pardon Iverson, so I did. It was the right thing to do.

(3.) April is Confederate history month, and governors of Virginia issue statements about that era of American and the commonwealth’s history. I decided to tell that story in a way most were not used to a governor of Virginia discussing the Civil War. Legendary Associated Press writer Bob Lewis later referred to how I had taken a different approach to writing about that war. I didn’t want it done in a romantic fashion — I wanted a discussion of the pain and suffering faced during that time. Since I was the governor, that is exactly what happened, because I had the power.

The accumulation and use of power matters — it must be done humbly and be used for the greater good — and it must be done after taking heed of how one gains broad-based, mainstream power. And black Americans are, indeed, getting more practiced at how to do that.

Am I saying we have done enough in this realm? Should we be satisfied with what he have done up to this point? Am I declaring victory? The answer to all three questions I just posed is, “No.” But we have a rough idea, concrete examples, of the difficult path it takes to be successful in the political and governmental arenas.

What must be done now is to search for and develop a template for how black Americans can achieve broader economic power.

That is important and needed because the veneer of elected political power without accompanying widespread economic power is not effective or sustainable.

We can point to black men who have led Fortune 500 companies, and many black men and women serve in significant leadership roles in corporate and non-profit America. But in many places where they work everyday they are a lonely breed, often standing as one or two in an organization of hundreds or more, forced to carry the hopes and identity of a people, with little help shouldering that burden. They can’t carry the economic future of an entire community on their backs in the small numbers that exist today.

They are the beginnings of the effort to create black economic power, but they need help. We must give it to them, for the health of black America, and all of America.

People often say that money is the mother’s milk of politics, and that is true. But it is more important to recognize that money is even more so the mother’s milk of pure power. And with effective economic power comes the ability to demand and sustain the equality gained from having political power.

How do we set our young people on the journey to achieving economic power? What is the key ingredient to grabbing and holding economic power? That is easy: Education is the key. No dumb person ever made a million dollars or saw it grow.

It is our responsibility to instill a value of education in the next generation. We have to do that. They have to see us reading. They have to see us involved in their homework and school life. They have to see us exhibiting a sense of curiosity that will become infectious. That is the main ingredient in economic power that we must stir in early, and nurture it to a lifelong simmer.

To paraphrase a famous saying: Where there is no education the people perish.

Where there is no education there is no economic power. And when there is no economic power, the gains that can be made by the exercise of political power will be ephemeral.

Have we “arrived”?

I happened to be scanning the TV last week and chanced upon an appearance at the Apollo theater in Harlem by Tracy Morgan, a comedian of color. I was shocked and stunned by what I heard. Not only did he make fun of and denigrate a number of young white women who have disappeared or been abducted or disappeared during the past several years, he then made a point to return to his schtick of disparaging people of color. And the mixed audience laughed and seemingly enjoyed what it was seeing.

Morgan said he had earlier gone to the White House and checked on President Obama, who assured Morgan that he, Obama, was still the nigger who knew what to do with the gun Obama was said to show Morgan when the president pulled his coat back to reveal a weapon. Morgan gleefully said something to the effect of how glad he is they we niggers know how to look out for ourselves. The audience roared its approval.

None of that performance was the least bit funny. You can’t simultaneously run with the foxes and hunt with the hounds. The masquerade of people like Morgan is over, it’s time to take the mask off.

Also on the TV screen that same night was an old Clint Eastwood movie, “A Few Dollars more.” Most of you are too young to remember that Hattie McDonnell’s portrayals of characters like the ones in “Gone with the Wind,” or Stepin Fetchit, Willie Best, Butterfly McQueen, and sad numbers of others. Those characters did not show our people in other than a denigrating light — as persons who lacked intelligence. But in 2011, people like Morgan now are doing was done during an earlier era, to paraphrase that Eastwood title, “For a Few Dollars More.”

Recently Philadelphia’s mayor, a man of color, spoke in his home church about the need for young people to dress, speak, and act in a more appropriate manner to better compete for good paying jobs. Mayor Michael Nutter is a member in good standing of that church. He was married there. He attends services there regularly. And despite those facts, he was chastised in an Op/Ed piece in the Philadelphia Inquirer for going too far by saying things I would call constructive criticism. Criticism that might save the lives of some young people or keep them out of jail.

And you know of the criticism heaped upon Bill Cosby when he called upon our young people and parents to show greater responsibility. That criticism has tuned 180 degrees since

Even though the people — black, white, and all colors of the human rainbow — elected a black man to be president the answer is, “No,” we have not arrived. And we can never be satisfied, otherwise any gains we have made will begin to melt into history. I don’t want to see that, and I am sure no one in this room does, either.

I found a shocking statistic, one that we all need to share with any and everyone who will listen: Former slaves, those freed by President Lincoln’s proclamation on January 1, 1863, could read and write at a higher rate 15 years after slavery than their descendants can today.

That is a damning, unacceptable fact. We cannot sustain political power if that remains true. We can’t create greater economic power if that remains true. Equality for no one in this nation is secure if that remains true, no matter their skin color.

We can do better than that, and we must. Doing so is properly living up to our responsibility to protect the American Experiment.

Have we “arrived”? A higher literacy rate among former slaves than the one that exists among black Americans today necessitates that the answer to that question is, “No.” But it should not freeze us in fear. It should be the fire that spurs us to action.

The story is told about the prophet Abraham being told by his sons that the wells of water that were so essential to their existence had dried up. The sons felt hopeless and forsaken. Abraham exhorted them to re-dig the wells.

We have work left to be done, but generations of giants before us did so much heavy work that we were able to see a black man elected president in 2008.

We can continue to do our part by making sure that other black men and women have the ability to read about it — and can support their children as we race to see whom the second black president will be. One of them will need to have the privilege of being the second who truly bestows the title, “first,” on Barack Obama — the second black president who establishes the pattern.

I am very happy to be today in Governor Deval Patrick’s Massachusetts, home of the second elected black governor. Thank you, and let’s re-dig the wells.